Collaborating with Patients to Design SDoH Integration

Patient Leadership – involving patients as co-designers of improved primary care – is a component of equity-oriented care. It ensures that time, energy, and resources will be directed toward interventions that effectively improve health and wellbeing. As primary care organizations integrate Social Determinants of Health (SDoH) strategies and interventions, it is essential that caregivers and community members with lived experience navigating inequities have an influential voice at the table. In this brief, we discuss the impact of patients’ involvement in the design of primary care-based SDoH work, as well as key recommendations and accompanying tools to effectively co-design healthcare improvement with patients.

Background

In May of 2018, 21 primary care teams joined forces with Health Leads in an 18-month learning collaborative focused on improving capacity to address patients’ essential resource needs. The curriculum for the Collaborative to Advance Social Health Integration (CASHI) presented patient leadership as a key driver of improvement.

In our experience, patient leadership has not been commonplace in social health programs. For example, at the start of CASHI in May 2018, only 5% of the 21 participating teams had structures in place to incorporate patient leadership into their social health programs. Through the collaborative, we sought to examine how methods for gathering and using patient feedback could be applied in the integration of social need interventions in the primary care setting and the impact on quality. By the end of the collaborative, in October 2019, over 70% of teams were incorporating patient input in their social need programs. Patients provided input into everything from social need screening practices to improving measurement, program design, and community partnerships. Patient leadership was also built into the collaborative structure itself, with each CASHI workshop on patient leadership co-led by a faculty member and one or more members of Health Leads’ Patient and Family Advisory Committee (PFAC). This paper outlines recommendations based on expertise in the field of consumer engagement as well as the experience and innovations from the CASHI community.

In this brief, when we talk about patient leaders as co-designers, we are talking about patients who are advocates or ambassadors representing others (e.g. on advisory councils or QI teams). A patient leader uses their health and social service journey to educate and empower others. Patient leaders are often storytellers, but they can also help gather or interpret data needed to understand a wider patient perspective and experience. Patient leaders also create new materials, identify new interventions and opportunities to improve processes. CASHI emphasized patient leadership to ensure primary care sites design and improve their SDoH programs with patients instead of for patients.

While the examples presented throughout focus on the value of patient leadership in social health integration efforts, our findings and recommendations from this work in CASHI align with known characteristics of successful patient involvement in program design, including bi-directional trust between patients and the organization, inclusion of diverse community perspectives, buy-in for patient leadership at multiple levels and valuing feedback.

CASHI teams used a variety of methods to engage patients in informing and improving their SDoH programs such as establishing or including existing Patient and Family Advisory Councils (PFAC). Teams also conducted surveys, focus groups, and some included patients directly in their quality improvement efforts. Specific strategies and their influence on their SDoH programs are described below (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Examples of CASHI Approaches to Patient Leadership and their Impacts on Social Health Integration

Recommendations

1. Ensure that the organization is receptive to patient feedback: Organizations must create a work environment that is receptive and emphatic towards patient participation. Communicate the mission of your PFAC and the benefits of patient engagement multiple times in multiple ways to all levels of the organization. Share success stories of how patient involvement in co-design has shaped improvements, new interventions, and positive outcomes in your newsletter and annual report. Advocate for funding to support the development of long-term structures like PFACs, and to make participation accessible to all marginalized patients.

For example, Virginia Commonwealth University Health (VCU Health) uses multiple approaches to support organizational level buy-in for patient feedback and incorporate it into daily activities.

- New patient onboarding stresses the need for two-way communication, mutual goal setting and patient team partnership.

- The Medical Director models desired behavior by asking patients for feedback daily and sets this expectation with the team.

- Feedback on unmet needs and community concerns is routinely solicited from patients and incorporated into operations.

- Discussion of patients’ feedback and concerns are incorporated into daily team huddles.

At VCU Health, the culture is shifting internally where staff and leaders commonly ask each other: “Have you asked a patient about that?” “Have you consulted our PFAC about that?” “Could patients be involved in co-designing that?”

2. Take action to include a diversity of perspectives: When building PFACs, or convening a focus group, recruit patients and families who have experience navigating barriers to the essential resources they need to be healthy. This may mean diversifying an existing board, and/or building a specific advisory committee for SDoH work. Intentional recruitment takes time, resources, and a sincere commitment to honor the social and intellectual capital that members bring to the table and is well worth it!

Example strategies:

- Ask existing PFAC members and Community Health workers for recommendations of local community organizers or community health advocates- e.g. fair housing advocates, disability rights advocates, health insurance navigators, or food justice organizers.

- Post fliers or interest cards in your clinic; ask patients to share fliers and interest cards

- Host focus groups or member meetings focused on SDoH programming, and recruit from these groups.

- Work with front desk or nursing staff who may be familiar with patients experiencing insurance and transportation barriers

3. Advocate for equitable compensation of patient leaders: When building patient leadership structures, compensation is an essential component. Patient leaders provide invaluable contributions and should be reimbursed for their time and effort. By establishing guidelines early on in the process, you can ensure everyone is fairly compensated.

4. Go beyond feedback for validation: create the conditions for meaningful collaboration : The importance of co-designing SDoH programs with patients cannot be overstated, however it is important to prepare as discussions around sensitive issues and stigma can be uncomfortable for both patients and care team members. And, this type of collaboration requires building bi-directional trust, which takes time to establish.

Support patients to effectively participate and share their stories

Most members of an improvement team, or participants in an improvement project, can benefit from an orientation to the tools and process being used. In particular, it is valuable to invest in orienting and training patient leaders to support them to share information in a way that will provide deeper insights behind the quality improvement data being discussed. For example:

- Truman Medical Center (TMC) offers a storytelling workshop to support patient leaders to develop skills like how to direct a story to different audiences, which elements to include, and self-care when sharing emotionally sensitive experiences.

- Virginia Commonwealth University Health’s (VCU) Complex Care Clinic PFAC typically selects one focus area to explore for every 6 months. For example, the group might spend 6 months focusing improvement on SDoH screening processes, tools, and measurement. This creates continuity and immersion in the language and concepts around a particular set of improvements

As patients are being recruited for a PFAC, it is important that before the work begins, the organization clearly communicates roles, responsibilities, and time commitments to patient participants, and periodically checks that the work is meaningful and valuable for the patients involved. Taking steps to communicate these details early, sets the precedent that patients’ time and contributions are valued by the organization and that these efforts are intended to be of value to both the organization and the patients themselves.

Additional considerations for creating the conditions for open and honest collaboration include:

- During meetings, normalize asking questions.

- Limit the use of acronyms.

- Provide references for tools and methods, as well as jargon glossaries.

- Mitigate power dynamics.

- Choose skilled facilitators, and facilitators with shared lived experience.

Finally, consider how to communicate how patient feedback was incorporated and used. This acknowledges to patients that their voices were heard and communicates to leadership the valuable contributions of these partnerships. For example, Oregon Health and Science University’s Primary Care Clinic at Richmond created a flier to communicate the purpose and work of their PFAC and included details on how feedback from PFAC members guided the evolution of their social determinants screener.

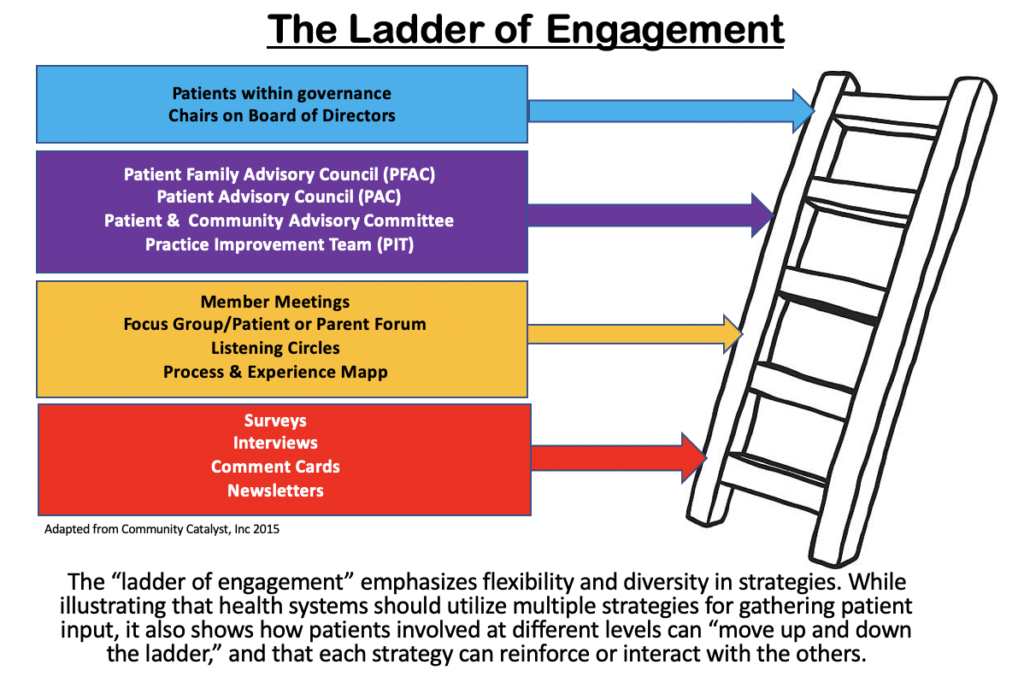

5. Use multiple strategies to support ongoing dialogue to foster trust between patients and care teams: Short-term engagements like surveys and focus groups should be used in addition to, and to reinforce longer-term engagements, like PFACs, to improve sustainability. Focus groups can provide more context and data for a project and are also an excellent source for new PFAC members. PFAC members, with adequate resources and support, can conduct surveys and interviews, and recruit other patient leaders. They can also potentially go on to join the board of directors. This pipeline of engagement opportunities is displayed in Community Catalyst’s “Ladder of Engagement” (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Community Catalyst’s “Ladder of Engagement”

For example, Truman Medical Center (TMC) has two formal long-term Patient Leadership models: a PFAC and Patient Champions, who participate on department or subject specific committees. TMC’s PFAC meets bi-monthly and patients participate for two years of service. The council addresses initiatives throughout the hospital, including those focused on SDoH.

Before launching their SDoH screening initiative, TMC interviewed 100 patients about which priority community needs to screen for. These interviews clarified three top areas: transportation, food, and affordable medications.

When Truman’s PFAC reviewed the new screening tool, they urged the hospital to clarify for patients why the SDoH screens were being administered and where the information would be stored. The PFAC originally proposed a poster campaign, but then instead created and added explanatory language to the screen itself: TMC SDOH Screening Form.

TMC’s PFAC also advises their strategy for gathering more patient feedback. The PFAC suggested that Truman create a landing page on their website for all things patient feedback. TMC Cares: The Patient Voice is now a portal through which patients can proactively engage in giving feedback to TMC or apply to be a Patient Champion or PFAC member.

Before launching their social needs screening pilot, Children’s Minnesota partnered with two clinicians to invite families to participate in interviews at the end of their visit. The main goal was to inform the screening tool and program workflow. Once the basic components of the program were up and running, the team set up space in the clinic lobby to survey families on how the hospital could best grow and improve the program – including what needs are most important to families, what barriers they experience, and what they look for when accessing community resources. Lastly, they organized a Listening Circle which provided the opportunity for a deeper dive into key questions on three topics: 1) community resources 2) program improvement and 3) program integration.

Conclusion

Investing in efforts to capture patient input and support patient leadership leads to the development of SDoH interventions that are better aligned with the needs of patients and the community and are more likely to lead to improved outcomes and patient experience. Patient leaders use their health and social service journey to educate and empower others, most often on advisory councils or QI teams. It is crucial to build sustainable relationships and go beyond feedback and validation. By truly engaging with patient leaders as co-designers, this allows SDoH programs to be created with patients instead of for patients.

Recommended Resources

The following resources are an accumulation of learnings and best practices our partners have shared throughout the years as they have incorporated patient leadership into social health programming. These tools are intended to provide first steps and considerations as you begin – or bolster – a Patient and Family Advisory Board at your organization. As always, these tools should be adapted to reflect your organization’s unique vision, values, and patient voice.

These findings were made possible by support from The Commonwealth Fund.